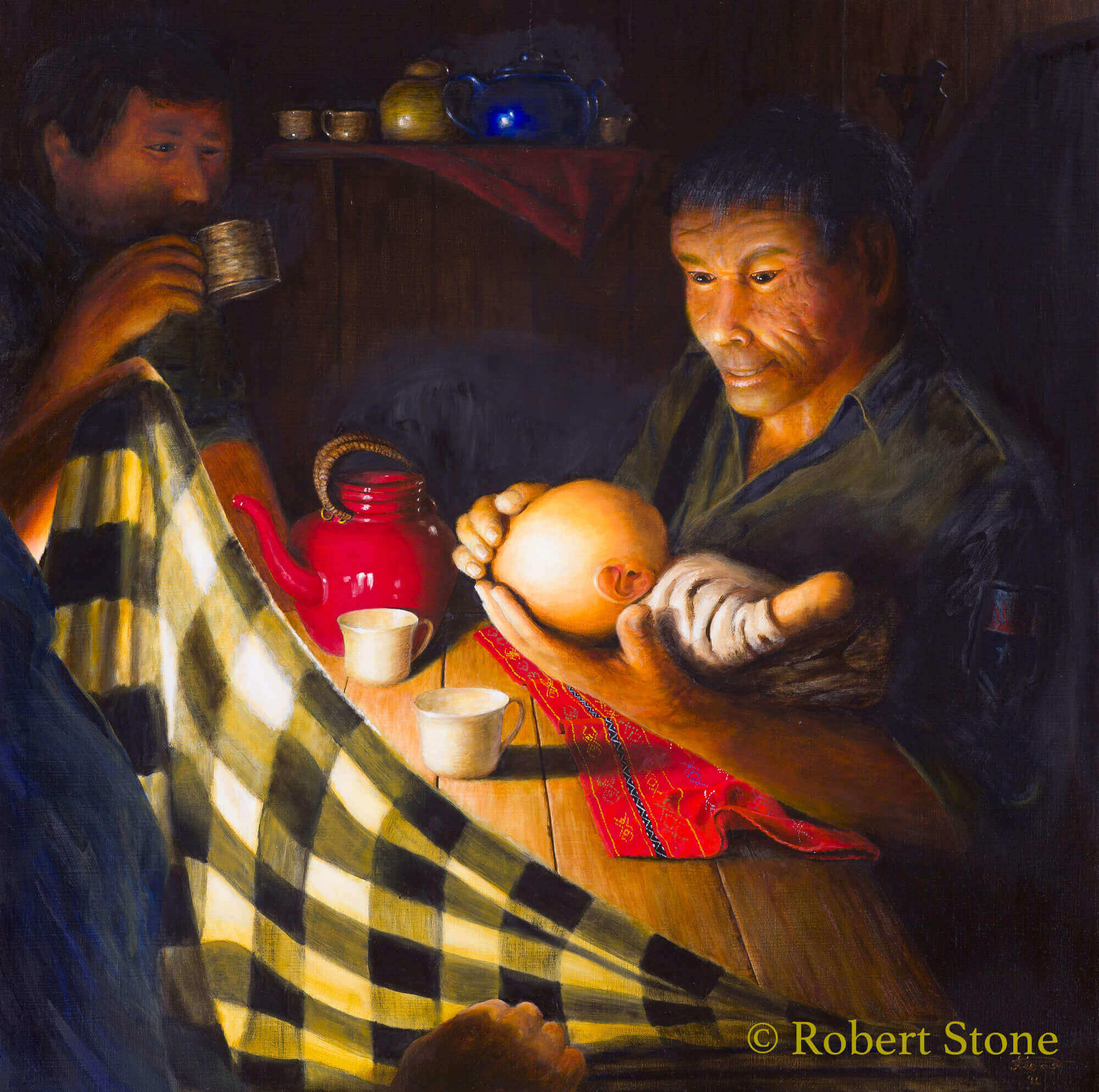

The Karen Sergeant and his Daughter

Po Paw Tah, Burma Border, 1993

I have always been struck by what a fine line there is between the monsters of the human race and its saints. I have been around both monsters and saints, and they are not so different. We all have both traits within ourselves. The only difference seems to be how we subtly nudge our impulses in one direction or the other, and which of our competing tendencies we choose to encourage in ourselves and our children as we mature as people. The Karen sergeant is one of the most unforgettable people I have ever met, as he fully embodies the two extremes in one person.

After having been arrested by military intelligence in Rangoon in 1991 (please see The Lady at Her Broken Piano), I had a lot of street cred with freedom fighters in Burma. I suddenly had access to areas in the rebel-held territories that I had not before. In 1993, I was allowed to visit the headquarters of the student army at Dawn Gwin and the headquarters of the Karen resistance of fifty years, the fabled jungle city of Manerplaw.

When I traveled along the Thai-Burma border in 1991, I spent a couple of hours in Po Paw Tah with a small group of tourists. Border crossings were illegal but common, and ours was arranged by the guest house in which we were all staying on the Thai side. The students had a propaganda hut set up in the village, but other than that my impression was of a very depressing hamlet of hot dusty paths pushing their way through rows of ramshackle bamboo huts, with a few people here and there wandering about sleepily with nothing to do.

I spent a week in Po Paw Tah two years later, and then my impression of the village was much different. In the evening, the village became alive and vibrant. Most of the soldiers of both the Karen and student armies returned from the jungle, the merchants and teashop owners lit up their establishments with candles and lanterns, and the generator was fired up at the makeshift movie house where they showed videotapes of Thai soap operas and melodramatic Burmese movies. I usually hung out in a teashop with soldiers from the student army, and it was there that I got to know H…T…

HT was an ethnic Karen who had been in the Burmese army. Most people in Southeast Asia are lightly built, but HT was tough and burly, with a broad chest, battlescars on his face, and a deep, gruff voice, fully fitting the part of the master sergeant that he was. My assigned overseer/guard/host in the village was a lieutenant who was a few years older than most of the students whose army he joined after taking part in the democracy uprising in 1988. A few years before that, HT had come with troops through his village in the central plains of Burma and had pressed my host into forced labor for a few days, terrorized him, and generally made his life unpleasant. Years later, they met again on the border, fighting for the same cause, instantly recognized each other, and became best friends.

HT growled his story to me one night over tea, his rifle slung over one shoulder, cradling his infant daughter in the other arm, with the candle light reflecting off the scars on his face. I don’t think I ever saw him without his rifle over one shoulder and his daughter cradled in the other arm.

He had come from a desperately poor family and had joined the army as the only way to improve his conditions. His activities did not always sit well with his conscience, but he justified his actions as soldiers do by saying it was his duty to follow orders. He knew that the very army that he was a part of had been fighting with his Karen people in the mountains for fifty years to thwart the Karens’ aspirations for autonomy, but he was somehow able to reconcile that enough to continue with his career. When the people rose up for democracy in 1988, HT was sent to Rangoon to help to put the demonstrations down. This was accomplished by the murder of over 3000 people over the course of a few days. At one point, HT was part of the army confronting thousands of mostly peaceful demonstrators on a street in Rangoon. He was ordered to open fire. His heart was with the demonstrators, but he knew that if he disobeyed orders his fate would be the same as theirs. He made a compromise within himself and ordered only one of the three units under his command to open fire.

As a result of his failure to fully carry out the order, he and his men were removed from the front line, and they were instead assigned to remove the evidence of the atrocities that were being committed by picking up the dead bodies and disposing of them. At first, they took the bodies to the crematorium of a nearby cemetery where they were thrown into the furnace, some being not yet quite dead. The furnace burned day and night and finally broke from the continuous heat. HT then was ordered to the reptile farm where his units hacked the bodies up and threw them into the snapping maws of the crocodiles. It was not long before the crocodiles could eat no more. At first at a loss as to what to do with the hundreds of bodies still left, a plan was eventually made and a huge barge was pulled up to the docks on the Yangon River. HT and his men were dispatched there, where they piled the rest of the bodies onto this barge. HT was told that it would be towed out to sea and then sunk. These were the bodies of the demonstrators who had been killed: college and high school students, both girls and boys; factory workers; monks and nuns; teachers; even members of the armed forces themselves, several whole units of which had disobeyed orders and joined the demonstrators.

Right after this, he deserted the army and made his way to the border, along with thousands of other Burmese citizens, to take up arms against the military government of Burma.

HT married a Karen woman in Po Paw Tah. Two months before my visit, his wife had delivered a beautiful baby girl and had died in the effort. I do not know who took care of the baby in the daytime, but in the evenings, when we got together in the teashops, she was never out of HT’s arms. I was touched by the contrast between his physical form and history, and the tenderness with which he cared for his daughter, cooing to her, caressing her, talking to her and trying to make her laugh. It was an obvious strain for him to control his emotions when the subject of his wife came up.

A few years after my last visit, there was a split in the Karen army. The Burmese government was able to cause this split by offering a deal to the Karens who had come from central Burma, who were mostly Buddhists like themselves, saying that if they came over to the dark side they would be given peace, money, and control of their ancestral lands. As a result, they broke away from the Karen National Liberation Army and formed the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army. Through their treachery, military force, and knowledge of the plans and locations of the KNLA, they and the Burmese army have since virtually destroyed the mostly Christian KNLA. Manerplaw, Po Paw Tah, and Dawn Gwin no longer exist.

To this day, I do not know which side HT chose.

*A note about the checkered cloth:

I hope that I will be excused for mixing cultural references here. The checkered cloth in the foreground is actually a symbol I borrowed from Hindu Bali. Poleng cloth represents good and evil. The cloth reflects the belief that there can be no good without evil, and the goal is to achieve a balance between the two. Just as a cloth that is merely black or merely white has no features, and the paper without the pencil line is merely blank and monotonous, creation has no meaning without both good and evil.

In the west we tend to see it differently. We try to promote the good and destroy the bad. Bad is to be eradicated until only good is left, perhaps a fool’s goal.

HT embodied both good and evil to an extreme degree.